The following comment in today's New York Times Magazine is better than just about anything I have seen in any scholarly treatise on the law of evidence:

The following comment in today's New York Times Magazine is better than just about anything I have seen in any scholarly treatise on the law of evidence:Evidence Some of our top intelligence officials are irritated at the way their analysts have been playing down reports from agents in the field of contacts between Hezbollah in Lebanon and Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. Gun-shy after criticism about past analyses of a series of contacts between Saddam’s Iraq and Al Qaeda, they are said to be “unwilling to make judgment calls.. . .We’re not in a court of law,” a source identified as “a senior United States official” told Mark Mazzetti of The Times. “When they say there is ‘no evidence,’ you have to ask them what they mean — what is the meaning of the term ‘evidence’?”

...

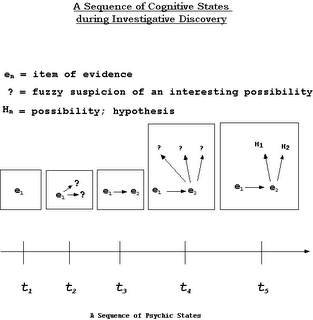

The job of a rhetorician is to answer rhetorical questions. I would sharpen the question, “What is the meaning of the word evidence?” by adding “and how is it different from proof?” Here’s an answer:

First, forget the cliché modifier credible; when it comes to evidence, what is believable to one analyst is incredible to another. Evidence may be hard or soft, conflicting or incontrovertible, it may be unpersuasive or convincing, exculpatory or damning, but with whatever qualifier it is presented, the noun evidence is neutral: it means “a means of determining whether an assertion is truthful or an allegation is a fact.”

But here’s the rub that rubs so many intelligence analysts the wrong way: Evidence — from tips, taps, tapes, testimony, confessions, weapons, documents, satellite photos and the like — is not in itself proof. Only the conclusion that experienced minds draw from a weighing of all the evidence can approach proof. With that requirement for human judgment understood, intelligence analysts can take their best shot.

No comments:

Post a Comment